Terminological Spaghetti: The Case Against Synonymising Fraud and Scam

- 15 hours ago

- 4 min read

It is well documented that fraud is the UK’s most commonly experienced crime (Westmore, 2023), is considered an issue of national security (Bath, 2021) and causes both financial and psychological harm (Carter, 2021) so comprehensive and far-reaching that it can be considered a public health issue (Hawkswood et al., 2022); one that authorities have a duty of care to safeguard against (Brown and Carter, 2020). The problem of fraud has also been widely reported in the media, particularly in cases commonly referred to in the UK as ‘Authorised Push Payment (APP) fraud’ - where a criminal manipulates a victim into sending money, often through a false romance, false investment opportunity, phishing communication, or having been deceived in an online shopping transaction (see e.g. Edwards et al., 2025; Hock and Button, 2023; Carter, 2024).

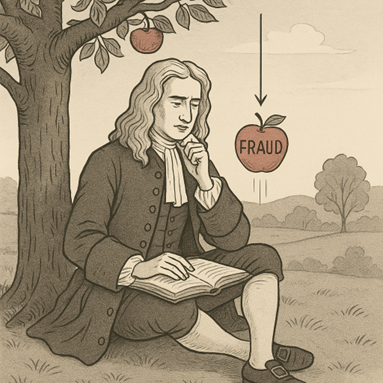

The media in the UK often describes fraud in their headlines as ‘cons’, ‘swindles’, ‘tricks’, and, as is the focus in our paper, as ‘scams’ (see e.g. Beard, 2024; Belcher, 2024; Parkin, 2024). Many academic articles follow the same trajectory, with publications often using the terms scam and fraud interchangeably (see e.g. Jung et al., 2022; Lacey et al., 2020; Rege, 2008). The interchangeability of terminology is brought into focus in the work of Taylor and Galica (2020) who propose that ‘frauds are scams whereby countless individuals have been tricked into conveying funds to a fraudster. . .’. An implication of this is that the way in which fraud awareness and prevention messaging is disseminated to the public has become distorted, in that the term ‘scam’ has often come to replace or be used interchangeably alongside ‘fraud’.

Why is this problematic?

From the offender’s perspective - criminals that perpetrate fraud often downplay and rationalise their offending. For instance, prisoner interviews with doorstep criminals reveal offenders denying causing harm to victims, claiming that the victims do not need the money and they aren’t physically injured (Phillips, 2016; Steele et al., 2001). This is particularly evident in the case of frauds originating in West African countries, where in-spite of the offending being economically motivated, offenders often seek to downplay and trivialise their offending for example by referring to it as a ‘game’ (Lazarus, 2018; Lazarus et al., 2025; Whitty, 2018) and justifying it as a response to colonial injustice and economic exploitation (Lazarus et al., 2025). The term ‘scam’ is associated with intellectual superiority and an activity to be admired and glamorised (Lazarus et al., 2023a, 2023b). Whittaker (2024, 173) found a novel example where a lecturer at a University in Cameroon openly joked with his students that were perpetrating fraud by commenting ‘I know those scammers in this class will know what I’m saying’, as a means of validating and accepting their actions.

From the victim’s perspective - Feelings of shame are also found to be a barrier to fraud victims reporting their experiences to the authorities (Cross, 2015, 2018; Parti and Tahir, 2023). Interestingly, a possible etymological origin of the term ‘scam’ can be traced back to the latin word ‘scōmm’, a later iteration of which is listed in the Imperial English dictionary (Ogilvie, 1882: pp. 794) as ‘Scomm’, defined as a ‘buffoon’ and to ‘mock’ and ‘jeer’. The continued use of the term scam to describe acts that amount to fraud is likely to result in these same feelings being engendered in victims.

What are the Implications?

The importance of using language that accurately reflects the reality of the criminal offence in public-facing communications is gathering apace. Most recently, INTERPOL has communicated to the world that the popular term ‘pig butchering’ should no longer be used in relation to romance-investment fraud hybrids, due to the harm this dehumanising term inflicts on victims of these crimes (Cross, 2024; Interpol, 2024; Whittaker et al., 2024). It poses a media-friendly alternative to ‘romance-investment fraud hybrid’ in ‘romance baiting’, crucially recognising the importance of capturing the public imagination, whilst offering a term (a range of terminologies to describe this crime is explored by Maras and Ives, 2024), that focuses on the context of the fraud rather than the pejorative term the criminals have for the victims. INTERPOL have also started to use ‘fraud’ rather than ‘scam’, driven by the recognition that the legal term should be used and that scam does not accurately represent the crime nor aid public or organisational understandings of it.

There is still a large body of communication from public bodies that draw on narratives of victim responsibilisation and blame; ‘don’t fall for a scam’ (Applebank.com, 2025)’, ‘don’t be a victim’ (Scamadvisor.com, 2025), ‘don’t make life easy for cyber criminals’ (City of London Police, 2025), ‘Don’t Let Imposters Part You From Your Money’ (Vista Capital Partners, 2025). These deliver expectations of an individuals’ ability to identify manipulation, recast having money criminally taken from you as the much more amicable ‘parting’ from it, conflate the crime as one of choice (‘letting’ it happen), negligence or stupidity (avoid victimhood by being ‘scam savvy’, Take Five, 2025) and as if it is a lack of thought, or a lack of self-protection that results in victimhood, rather than a result of manipulation, grooming and abuse.

Our message is simple – that we should call a fraud a fraud.

Comments